Barnacle goose population studies

Ecology Consulting has been carrying out research on Barnacle Geese on Islay since 1984, in one of the UK’s longest-running ornithological studies. Over 40 years almost 10,000 geese have been individually marked and their life-histories followed during our regular visits to the island (with 175,000 sightings to date). We have also been helped by a network of observers across the range to better understand the birds’ movements and survival.

Our publications include:

Agricultural damage and barnacle geese - Percival and Houston 1992 Journal of Applied Ecology

Grassland management for geese - Percival 1993 Journal of Applied Ecology

Population structure of Islay barnacle geese - Percival 1991 Ibis

Spring staging areas of barnacle geese in Iceland - Percival and Percival 1997 Ecography

Autumn staging of barnacle geese on Islay - Percival et al. 2020 Scottish Birds

Scaring as a Goose Management Tool - Percival et al. 1997 Biological Conservation

Review of the Islay Goose Management Scheme - Percival and Bignal 2018 British Wildlife

Impact of avian influenza on barnacle geese - Percival et al. 2025 Bird Study

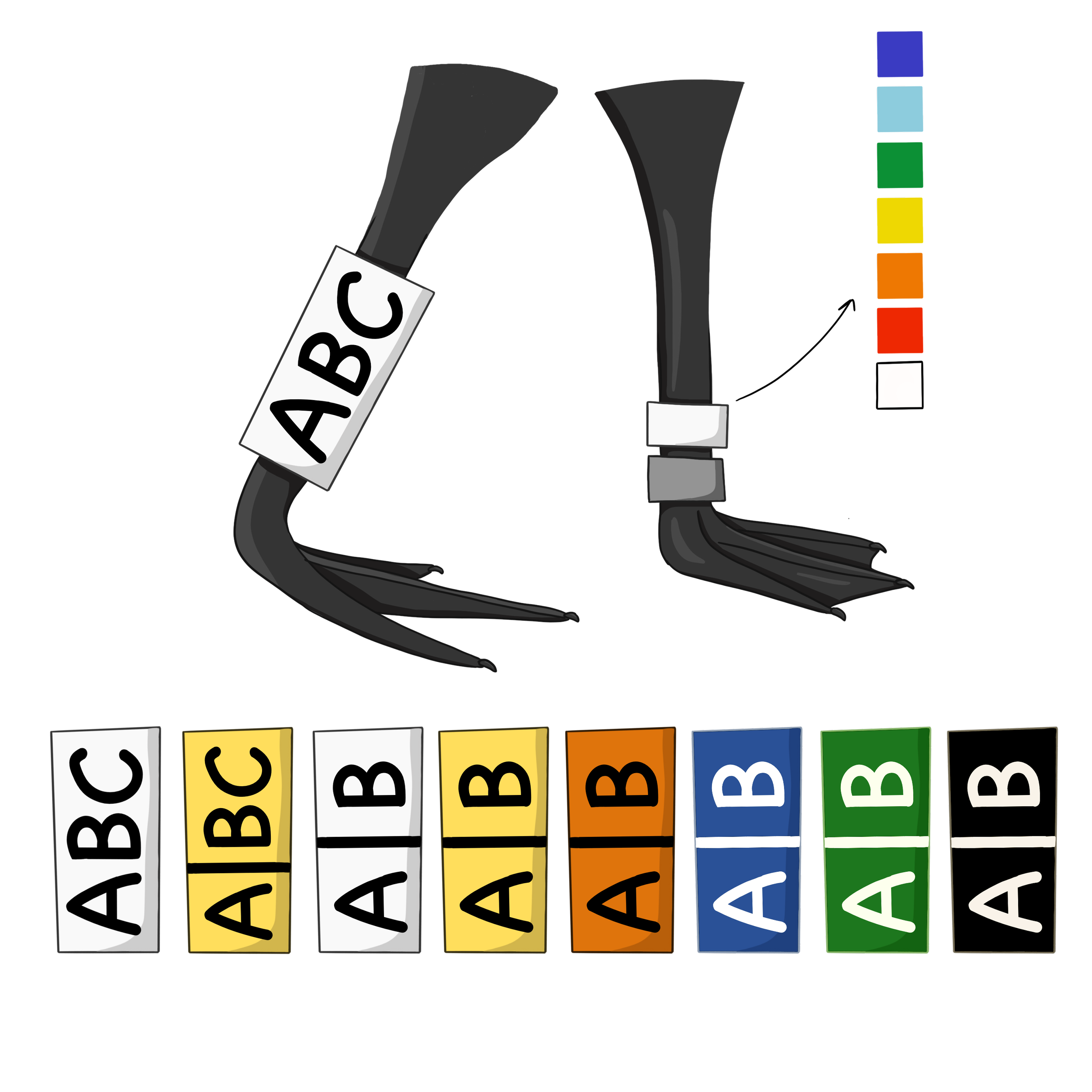

BARNACLE GOOSE RINGS IN THE GREENLAND/ICELAND POPULATION

Greenland Barnacle Geese have been individually marked with engraved darvic rings since the late 1960s. Birds historically have been ringed mainly on the breeding grounds in Greenland, on Islay, and on the Inishkea Islands off the west coast of Ireland. Most have used white 3-character darvics (black text on white rings), with colour rings often used over the BTO metal to mark catches and help identify individuals. Darvics can be three letters, number-letter-letter or letter-letter-number.

More recently, geese have also been ringed on the new breeding grounds in Iceland, during the post-breeding flightless moult period, These have used a range of colour darvics, engraved with 2- and 3-letter codes. All are uniquely identifiable by a solid line around the ring after the first character.

If you see any of these rings please let us know and we will send you their full sightings histories. All we need to know is:

Bird ID code, Date and Location (e.g. OS grid 6-figure reference), any colour rings (and which legs the rings are on).

Just email the details to us at: steve.percival@ecologyconsult.co.uk

DO BARNACLE GEESE CAUSE AGRICULTURAL DAMAGE?

Percival S. M. and Houston D. C. 1992. The effect of winter grazing by barnacle geese on grassland yields on Islay. Journal of Applied Ecology. 29:35-40.

We aimed to assess the effect of goose grazing on silage yield and examine the relationship between barnacle goose grazing intensity and grassland yield on Islay. We measured dropping density as a measure of goose grazing intensity and grass yields between grazed and ungrazed plots, using exclosure cages to create control plots.

At the end of April, immediately following goose migration north from Islay, all fields had significant yield losses attributable to goose grazing. We found a significant reduction in yield in both study years then, with a significant positive correlation between yield loss and grazing intensity, but only accounting for 28% variation in yield loss (indicating other factors were important as well in determining grass yield).

June silage yield losses were, however, not as proportionately large. Goose grazing was a major influence on silage yield but the time since reseeding and year were also important factors. Differences between years highlighted greater complexities in the relationship and were partially attributable to weather conditions. June grass yields had the same negative correlation with overwinter goose grazing, but a smaller proportion of variation was explained by goose grazing intensity (19%).

how should grasslands be managed for barnacle geese?

Percival S. M. 1993. The effects of reseeding, fertilizer application and disturbance on the use of grasslands by barnacle geese and the implications for refuge management. Journal of Applied Ecology. 30: 437-443.

We aimed to investigate effective grassland management strategies on the RSPB reserve at Loch Gruinary, Islay (mixed grasses reseeding, nitrogenous fertiliser application and human disturbance) to support as many geese as possible during winter on Islay. We counted dropping density to measure goose activity and compared numbers between paired fields of different experimental groups, in relation to reseeding, fertilizer application and distance from public roads.

Reseeding and fertiliser application increased goose numbers using experimental fields but did not affect numbers on the reserve as a whole, concentrating local birds in improved fields rather than attracting geese from elsewhere on the island.

Recently reseed pastures supported significantly higher goose numbers (up to 60-135%) but significantly less in their second and third years, and significantly higher than old pastures without any reseeding. Fertiliser application increased grazing intensity, but to a smaller extent (17-42%) and was not consistent in all fields each year. Disturbance had the smallest impact on feeding site choice with only a small area of the RSPB reserve affected. We found only a slight decline in dropping density closer to the road, even only 25 m from its edge, showing road vehicles had little impact on birds’ overall feeding site selection. There was a combined effect of road proximity and overhead electricity wires as dropping densities declined by 45% compared to the field maximum.

barnacle goose population structure

Percival S. M. 1991. The population structure of Greenland Barnacle Geese Branta leucopsis on the wintering grounds on Islay. Ibis. 122:357-364

Greenland Barnacle Geese on Islay revealed site-faithful behaviour, with most remaining on a restricted group of sites during a single winter and in consecutive ones.

We aimed to determine whether Islay’s wintering population of Greenland Barnacle Geese was structured into sub-groups or distributed randomly around their wintering ranges and if there was any relation to their summering areas. We observed and monitored individually marked birds with darvics through the winters of 1984-87 (following previous cannon netting and catches while flightless).

By using cluster analyses and assigning site groups, we found the proportion of the total goose population at each site generally remained consistent between years and most groups. Most birds remained faithful to their site group between seasons and across the four years, with only 15% of females moving further than the site used in the previous year or the one adjacent.

SPRING STAGING IN BARNACLE GEESE IN NORTHERN ICELAND

Percival S. M. & Percival T. 1997. Feeding ecology of barnacle geese on their spring staging grounds in northern Iceland. Ecography. 20: 461-465.

We aimed to investigate the feeding ecology of the Greenland-breeding population of barnacle geese on their spring staging grounds in northern Iceland. Through extensive surveys across northern Iceland, we mapped habitats and individually ringed birds, and recorded feeding behaviour.

Total numbers were similar across the study years but specific sites showed major differences. Grassland habitats were used very frequently (<98% in both years), and the proportion of geese on improved pasture was far greater than its availability. 88% of their time from 3:30 to 23:30 hours was spent feeding, for almost the maximum amount of time available, with no significant differences between years. The area of improved grassland was the most important factor determining goose numbers a site supported. Spring staging was shown as vital for their food intake, for the geese to increase body reserves in prepartion for further migration to Greenland and breeding.

IS SCARING A USEFUL TOOL IN GOOSE MANAGEMENT?

Percival S. M., Halpin Y. & Houston D. C. 1997. Managing the distribution of barnacle geese on Islay, Scotland, through deliberate human disturbance. Biological Conservation. 82: 273-277.

A disturbance programme on Islay showed ~50% reduction in goose numbers in disturbed areas, increased movement to undisturbed sites and slightly increased immigration rates, but many individuals persisted in using heavily disturbed sites.

We aimed to investigate the influence of deliberate human disturbance on the fidelity of bird groups on Islay. We used an experimental scaring scheme in 1987-88 with people approaching feeding geese until they flew away, in combination with gas guns and plastic tapes to further discourage feeding. Bird counts and resightings of individually marked birds allowed estimations of between winter fidelity, between and within winter immigration, fidelity and movement across the island. Data collected in the previous two baseline years was used to compare bird behaviour.

Between winter fidelity, immigration and movement within Islay overall showed no significant differences before and during the scaring scheme. Birds using the scaring zone were generally less site faithful than those using refuges but this was not affected by the scaring scheme. A core of geese remained faithful to the scaring zone, despite the scaring activity. Fidelity to the scaring zone was, though, much lower in 1987/88 than in the previous winter, with greater movement and slightly higher immigration.

There was no indication of reduced breeding performance of geese that were more regularly disturbed throughout the winter in the short term.

The scaring was successful in its main aim of moving birds to refuge areas but needs longer-term study as it could result in poorer body condition if birds were unable to compensate for greater energy expenditure, and may not be economic (potentially costing more money than saved in grassland yield).

THE ISLAY GOOSE MANAGEMENT SCHEME: IS IT ACHIEVING ITS OBJECTIVES?

Percival S. and Bignal E. 2018. The Islay Barnacle Goose management strategy: a suggested way forward. British Wildlife. 30.1: 37-44.

Islay holds 60% of the global population of Greenland Barnacle Geese, but this has led to local conflicts with farmers due to agricultural losses. A new scheme was launched in 2015 to allow active culling of barnacle geese and reduce their population from 42,000 to a target of 25-30,000. We reviewed the management scheme and concluded that culling does not deliver long-term sustainable and cost-effective solutions.

We highlighted agricultural damage was not directly proportional to the number of geese grazing a field. The scheme failed to deliver the best value for money, raised animal welfare issues and created long-term lead-poisoning risks to birds, wild animals and livestock grazing on areas shot over. We believe reassessment is necessary and should incorporate effective refuge areas; determination of disturbance impact across Islay and at a whole Greenland population level; evidence-based modelling of bird distribution and population change rather than predictions; investigations of lead introduced into the environment and subsequent consequences; and better involvement of interested stakeholders.

AUTUMN STAGING OF BARNACLE GEESE ON ISLAY: HOW IS THE ISLAND LINKED TO OTHER SPecial protection areas?

Percival S. M., Cabot D. and Colhoun K. 2020. Numbers and Distribution of Autumn-Staging Barnacle Geese on Islay and their Exposure to the Islay Goose Cull. Scottish Birds.

We aimed to provide new information on the numbers and distribution of Greenland Barnacle Geese that stage on Islay in the autumn, and how these are affected by the culling that forms part of the NatureScot Islay Goose Management Scheme. By utilising ongoing long-term studies with individually marked geese and resightings during autumn 2018 and 2019, we observed a high proportion of geese caught outside Islay using the island for autumn staging. Most of these non-Islay geese (61-73%) were found in the Gruinart area, where shooting is reduced in autumn, but important numbers were also using other parts of the island where they would be vulnerable to shooting.

The Islay Goose Management Strategy must be reviewed to protect the integrity of other SPAs outside Islay, as many birds are exposed to culling. Islay is important in an ecologically coherent network of sites for Greenland Barnacle Geese, so without further attention, it could have adverse effects on SPAs designated to protect this species.

AVIAN INFLUENZA IN BARNACLE GEESE

Percival S. M., Bowler J., Cabot D., Duffield S., Enright M., How J., Mitchell C., Percival T. and Sigfusson A. 2025. Spatial and temporal variation in mortality from avian influenza in Greenland Barnacle Geese Branta leucopsis in their wintering grounds. Bird Study. 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00063657.2024.2439179

More than 20% of the Greenland Barnacle Geese population was lost due to avian influenza (H5N1), but this varied between wintering location and through time.

We aimed to investigate mortality patterns in wintering Greenland Barnacle Geese, quantify avian influenza’s impact and evaluate the implications for future population management strategies. We utilised our comprehensive dataset of marked individuals spanning three winters before the initial outbreak (2018-19 to 2020-21) and two winters during the outbreak (2021-22 and 2022-23) across five locations: Islay, Argyll, Inishkea, Mayo, Balygilgan, Sligo, Tiree, Argyll and North Uist, Outer Hebrides. Ongoing monitoring provided goose numbers and we carried out additional carcass searches.

By calculating apparent survival rates and excess deaths, we found that Islay, Tiree, and Sligo experienced severe mortality, with survival rates reduced by 30-56%, while Uist and Mayo showed little or no impact. We also found differences in outbreak timing, with Sligo affected mainly in March 2022, while Islay and Tiree experienced the main outbreak in November/December 2022 and February/March 2023, respectively.

The impacts of the recent avian influenza outbreak demonstrated mortality rates sufficient to cause population-level impacts. We estimated 11,300 excess deaths on Islay during the peak outbreak, 2,200 in Sligo and 1,900 on Tiree, contributing to an overall loss exceeding 20% of the global population.

We highlight the critical need for dynamic population management strategies to prevent major population declines and instead enhance their resilience. We recommend that individually-marked bird records should be incorporated into future monitoring; management schemes should be adaptive and rapidly respond to population threats; existing population modelling should include catastrophic events such as avian influenza outbreaks; and goose management thresholds should be reviewed to support population resilience.